The Sin of the Orthodox

Making Idols out of Fig Leaves

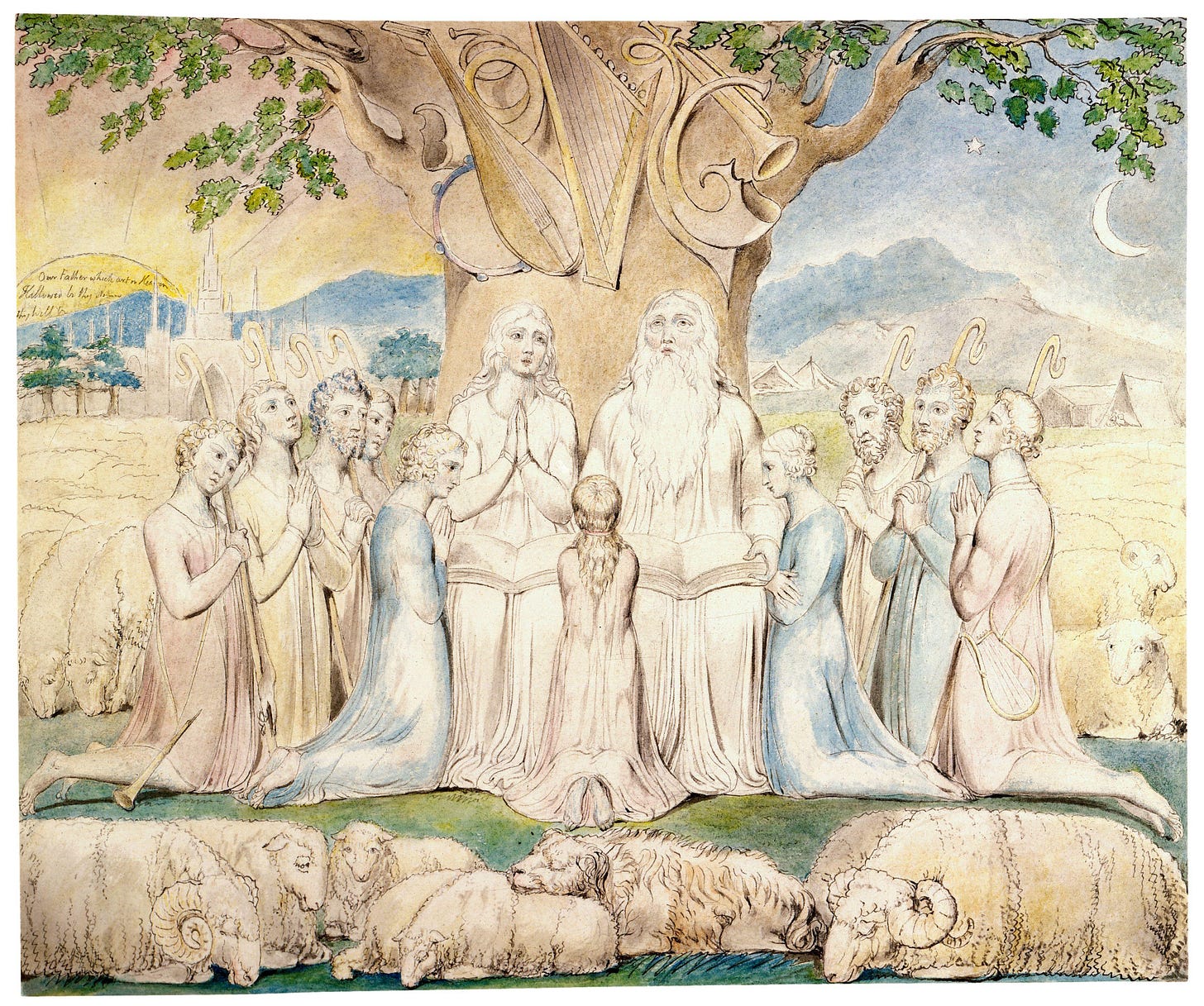

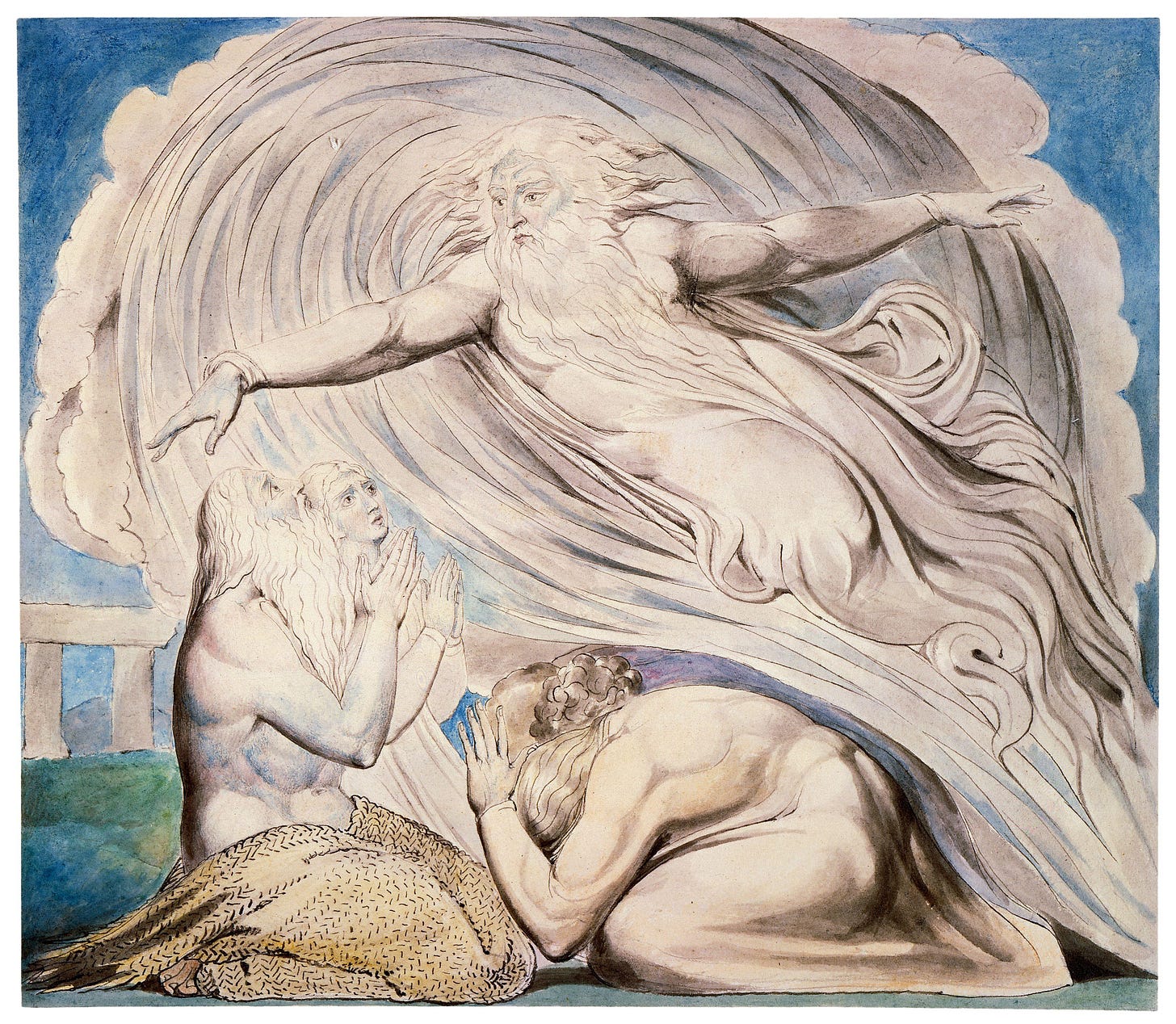

Note: by “Orthodox” I am referring to those who are biblical and traditional in their theology; I am not referring to the Orthodox Church. Also, the illustrations are from William Blakes great engraved prints on the book of Job (1826).

• • •

Each time I read the book of Job I find deeper meanings. One idea that keeps coming to my mind is the sin of those who thought they had God all figured out. In particular I mean the friends who came to “comfort” Job. As it turns out, they were more interested in confronting Job, who ends up calling them, “miserable comforters” The main part of the book is a debate between these three “teachers” and Job about the justice of God.

The substance of their great debate could be summarized this way:

The friends argue that since God is just, Job’s afflictions must be the punishment for some hidden sin.

Job argues in response (repeatedly): Look, I don’t have any “secret sin” that deserves this kind of punishment, so God is not being just to me.

The friends then accuse him of undermining the notion of God’s justice.

Job responds by repeating what he knows: I am innocent, yet enduring incredible suffering, and this suffering seems to come from God himself. Therefore, “God is not being just with me”.

Now, of course, we readers are let into a secret. Chapters one and two describe the scene in heaven where God twice describes Job, “a blameless and upright man, who fears God and turns away from evil”. In fact, God says, “there is none like him on earth”. So we know before the dialogue begins that the three friends are in the wrong. Job’s afflictions are not punishments. Job is blameless before God.

But imagine if we did not have this information. Imagine we walked in to the story right where the dialogue starts. On the one hand, we have three wise, older men who have an exalted view of God and are eager to defend his ways. They are completely orthodox in their understanding, and their first priority is to protect God’s reputation. On the other hand, you have Job, who seems to be not only suffering, but positively afflicted by God (the suddenness and completeness of his losses cannot be mere coincidence). Job argues that he is blameless, therefore God is not being just, while the orthodox friends argue that God is just, therefore Job is not blameless. Who is right?

Whose side (honestly) would you be on?

Wait: before you answer, again try to strip your mind of what you know from chapters one and two. And you may find yourself in the position of Elihu. Elihu is a rather mysterious figure. He shows up without introduction and his name is not mentioned again after his long speech (chapters 32-37). His speech does not serve to advance the dialogue at all, and neither God nor Job nor the friends respond to it.

Here is what I think: Elihu is intended to function as a warning to the reader. His viewpoint and speech (“Job, you are wrong; I know wisdom, and you are speaking folly”) are the natural conclusion we are tempted to draw simply by listening to the speeches (without the prologue). In his speeches, he not only agrees with the orthodox friends, but is angry at them for not being able to withstand Job’s arguments.

It is right after his speech that God Himself arrives on the scene and, incredibly, joins in the argument. God does two things.

First, he reproves Job (chapters 38-41) for failing to understand what Kierkegaard would later call “the infinite qualitative distinction” between God and man. Job is wrong because He simply is not in a place to understand God’s ways, and therefore is recklessly hasty in saying that God is unjust to him.

The second thing God does, then, is surprising. He approves Job, especially in contrast to his orthodox friends. Twice he tells the orthodox, “you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has”. In fact, God regards this not only as a mistake, but a sin, for which they need to offer a sacrifice and ask Job(!) to pray for them. God seems less upset by Job yelling at Him than the friends yelling at Job on God’s behalf.

This, then, is the surprising conclusion to the dialogue: God and Elihu are contrasting figures, even though Elihu represents the orthodox views about God. Elihu listens and takes the side of the orthodox friends and rebukes Job, while God listens and ultimately takes the side of Job and rebukes the orthodox.

And this is the heart of the book of Job: God’s ways are, in the final analysis, not able to be fully understood by man, simply because we are never in the position that He is in. Even the most godly (like Job) and the most orthodox and cerebral (like Job’s friends) can never understand God in the same way they understand the things of this world. In fact, God describes the words of the orthodox friends, who felt they were speaking godly wisdom, as “folly”.

Now, here is where the rubber hits the road. I have always taken pride in holding correct, orthodox views of God and theology. And I still feel that the biblical viewpoint is the best way to understand the world in which we find ourselves in. Yet, books like Job warn me to be very humble about my understanding. In the end, I have little doubt that my orthodox, evangelical theology will be like the fig leaves Adam and Eve used to clothe themselves: wholly inadequate, and replaced by something else by God’s grace.

What does this mean practically? It means that we should be careful that our study of theology should never outstrip our understanding of “the infinite qualitative distinction”. It means our eagerness to defend God should never come at the expense of loving people. It means we must learn to live out our worldview fully, all the while realizing that when we see Him all of our previous “knowledge” will be fig leaves of foolishness.

Love this, Job is one of the books I've always struggled with. I may still struggle with it but at least I have a new perspective to look at it with.

Hopefully this makes sense, it did in my feeble brain so there it is. 🤔

Wow, Beautiful!

Certainly, my knowledge of God is very limited.

Suffering: I still don't understand why Job had to suffer so much; but the Lord loved Job because he was a righteous man and because job worshiped the Lord as his Savior.