The Two Pietas

Their differences illustrate in eternal stone the spiritual journey of the great artist.

In June of 1496 a 21-year-old sculptor arrived in Rome and within a month received a commission: a statue of the Roman wine god Bacchus, for Cardinal Raffaele Riario. However, the work was rejected by the cardinal, and the young sculptor began to look for another commission.

Soon the French ambassador to the Holy See, Cardinal Jean de Bilhères-Lagraulas, commissioned him to carve a Pietà, a sculpture showing the Virgin Mary grieving over the body of Jesus [pieta = pity]. The piece was finished within two years, and was soon to be regarded as one of the world's great masterpieces, "a revelation of all the potentialities and force of the art of sculpture". Thus, by the time he was 24, the name of Michelangelo was in the forefront of European art.

Michelangelo sculpted the Pietà from a single block of Carrara marble, which he claimed was the most perfect block of marble he had ever worked with. He also claimed that he could “see” the sculpture, and needed only to remove the marble surrounding the scene.

I traveled to Rome some years ago to gaze at the statue I had adored in pictures all my adult life; It seemed to me the most perfect of all sculptures. I could have spent the whole afternoon there, staring in wondrous silence. My patient daughter smiled at me as an adult daughter might smile at a long-widowed father who has fallen in love.

As a work of technical skill, the Pietà has no equal. Contemporary opinion was summarized by Vasari:

“It would be impossible for any craftsman or sculptor, no matter how brilliant, ever to surpass the grace or design of this work, or try to cut and polish the marble with the skill that Michelangelo displayed. It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have reduced to perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh. Michelangelo put in to this work so much love and effort (something that he never did again), that he left his name written across the sash over Our Lady’s breast.”

Staring at the Pietà, I could not help but agree with Vasari. The scene looks less like stone than ivory. Or, if not that, stone in an almost liquid form. One senses it is almost too perfect. Or, rather, it is a perfection of an ideal, that is, a Platonic ideal.

For Plato, contemplation of the beautiful form led to a greater understanding of the essence of reality, and an ascent to the transcendent realm, the world beyond this world of matter.

As Catesby Leigh notes in a wonderful essay in First Things, much of Michelangelo’s early works,

…reflect Plato’s interpretation of eros in his Symposium, which Michelangelo must have encountered after entering the household of Lorenzo de Medici at age fifteen, when he was already recognized as a prodigy. Another member of Lorenzo’s household was the philosopher Marsilio Ficino, a renowned scholar and priest who, as one of the principal thinkers of Renaissance humanism, endeavored to harmonize Platonism with Christian belief. The young Michelangelo was imbued with the conviction that the contemplation of beautiful forms can serve as a step on a ladder that leads man out of the world of the flesh and into the realm of the spirit.

This is why, despite the subject matter, there is an idealized peace and harmony about the Roman Pietà. Indeed, this could be the only criticism of the piece. The quote from Vasari above even hints at this: “a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh”. And the perfection of the human forms seem little touched by the manner of Jesus’ death. The wounds on his hands and feet are minuscule; the torso bears no marks from the whip, nor the brow from the crown of thorns; he could almost be sleeping or lying in calm repose. Mary, although looking down on her murdered son, nevertheless appears at peace. The two figures appear idealized despite such sorrow, reflecting the Neo-Platonic ideals of beauty on earth reflecting God’s beauty; the beautiful figures of the Virgin Mary and Jesus are echoing the beauty of the Divine.

Michelangelo was much criticized for making Mary so lovely and young, instead of a middle-aged peasant woman. But Michelangelo was not stiving for historical accuracy, but for the ideal, the transcendent, the eternal. Mary and Jesus represent, at this level, not murdered son and grieving older mother. Rather, they represent idealized man and woman, together, in their triangular unity, reflecting the image of the Triune God.

Catesby Leigh: “Michelangelo knew that man is the cosmic point of intersection between the realms of matter and spirit. The structure and proportions of the human body are integral to God’s supreme organic creation, and therefore the human figure is art’s supreme symbolic form.”

Michelangelo himself put it this way:

Every beauty which is seen here below by persons of perception resembles more than anything else that celestial source from which we all are come...

My eyes longing for beautiful things together with my soul longing for salvation have no other power to ascend to heaven than the contemplation of beautiful things.

This is the thought that guided his hammer and chisel: beauty, especially of the idealized human form, is a both a reflection of God's beauty and a climbing pathway in which the person of perception may ascend, in some way, to heaven itself.

I gazed at the Pietà until the guards began closing St. Peter’s. My daughter asked if I wanted a picture with it. I declined. It seemed disrespectful. As we went out into the night, I thought I would never see another work of human hands that would move me the same way.

I was wrong.

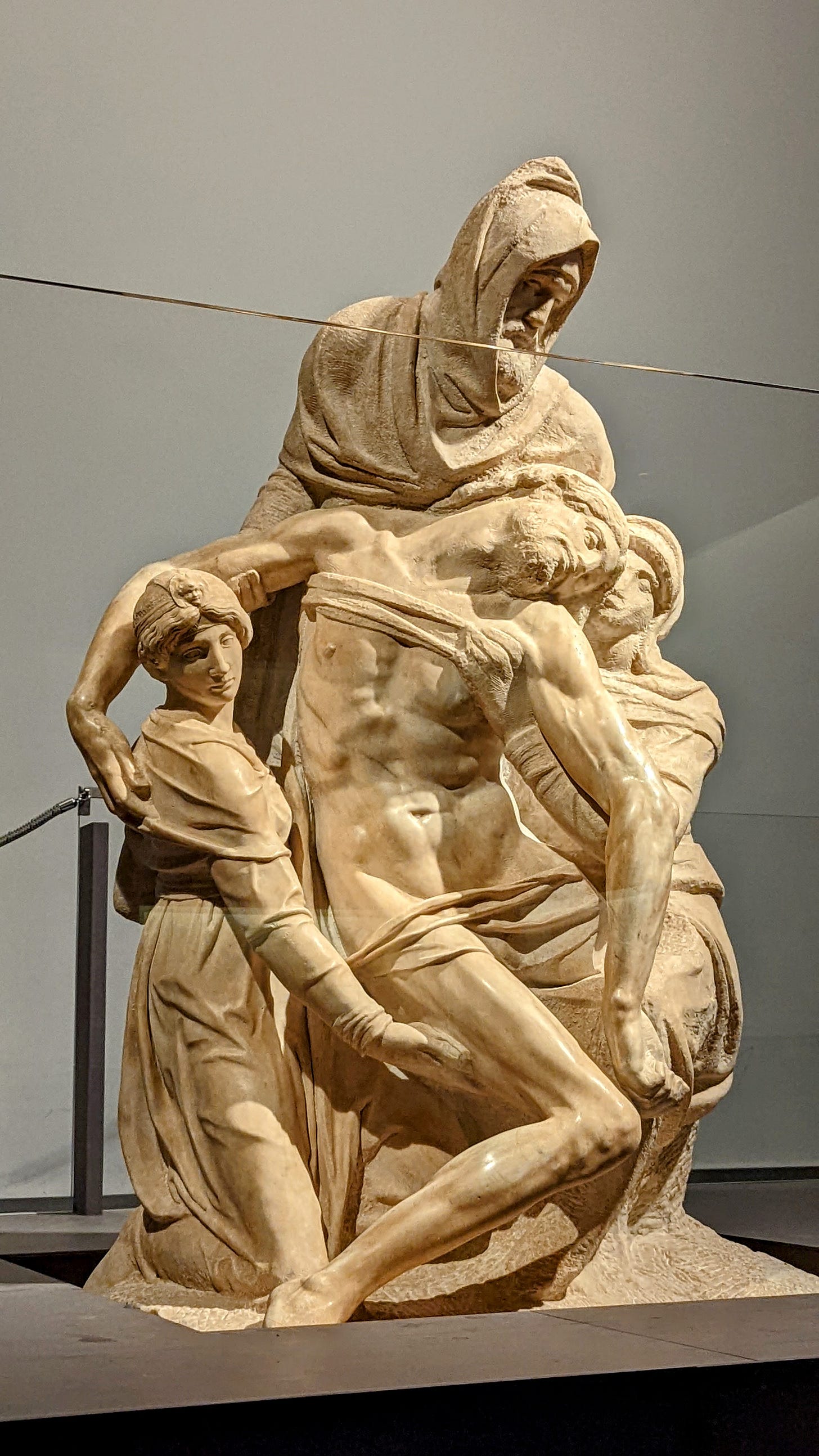

I was soon to wonder at another Pieta, also from Michelangelo, but made at the end of his life; It is quite unlike the first. Its differences illustrate in eternal stone the spiritual journey of the great artist.

Near the end of his life the great artist Michelangelo began work on another Pietà, utterly unlike the one he completed at age 24.

Fifty years had passed since Michelangelo had completed the Roman Pietà. No one remains unchanged in their thoughts and values over half a century, especially a person with a mind like Michelangelo’s. Always a religious man, his maturing years had brought a maturing spirituality, and a deepening ambivalence about what art is for, and what it can do.

At the age of 61 he began a deep friendship with a 46-year-old poet, Vittoria Colonna. The great artist addressed some of his finest sonnets to her, made drawings for her, and spent long hours in her company. Vittoria became his been deepest confidante, and every Sunday afternoon they sat on a balcony at the convent where she lived in Rome, discussing the deep theological questions of the day: What is the nature of grace? What is the nature of sin? Who has religious authority on Earth? They had watched the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation first-hand, and they were both keenly interested in theology.

Colonna also conveyed to him the intellectual and religious concerns of her scholarly, cultured, very catholic circles of friends, including clerical reformers within the Catholic Church, who were seeking to heighten religious awareness and personal holiness.

In 1547 Colonna died, leaving Michelangelo bereft. He was also buffeted by the ailments of age, guilt over unfinished projects, and disillusions over the treachery of friends.

He turned to poetry, picturing her as a great fire, warming his old age.

But Heaven has taken away from me the splendor

Of the great fire that burned and nourished me;

I am left to be a coal, covered and burning,

And if Love will not offer me more timber

To raise a fire, in me there will not be

A single spark, all into ashes turning.

In the year Colonna died, Michelangelo would begin work on a new Pieta. This was to be something special to him, a final coda giving a backwards meaning to all he had done before. He worked, not on commission, but after hours, in privacy, wearing a thick hat holding a candle for illumination. This pieta would go on his own tomb. And, for the first time, he carved his own face into a sculpture.

He never finished. In fact, in his 80th year, after working on it for over half a decade, Michelangelo would take a hammer and chisel and begin to destroy it. Vasari, his first biographer, says only the intervention of a servant saved it from total damage.

Michelangelo reluctantly allowed the pieces to be gathered and later restored by another sculptor, who also added the face of Mary Magdalen (in an unfortunately passive expression).

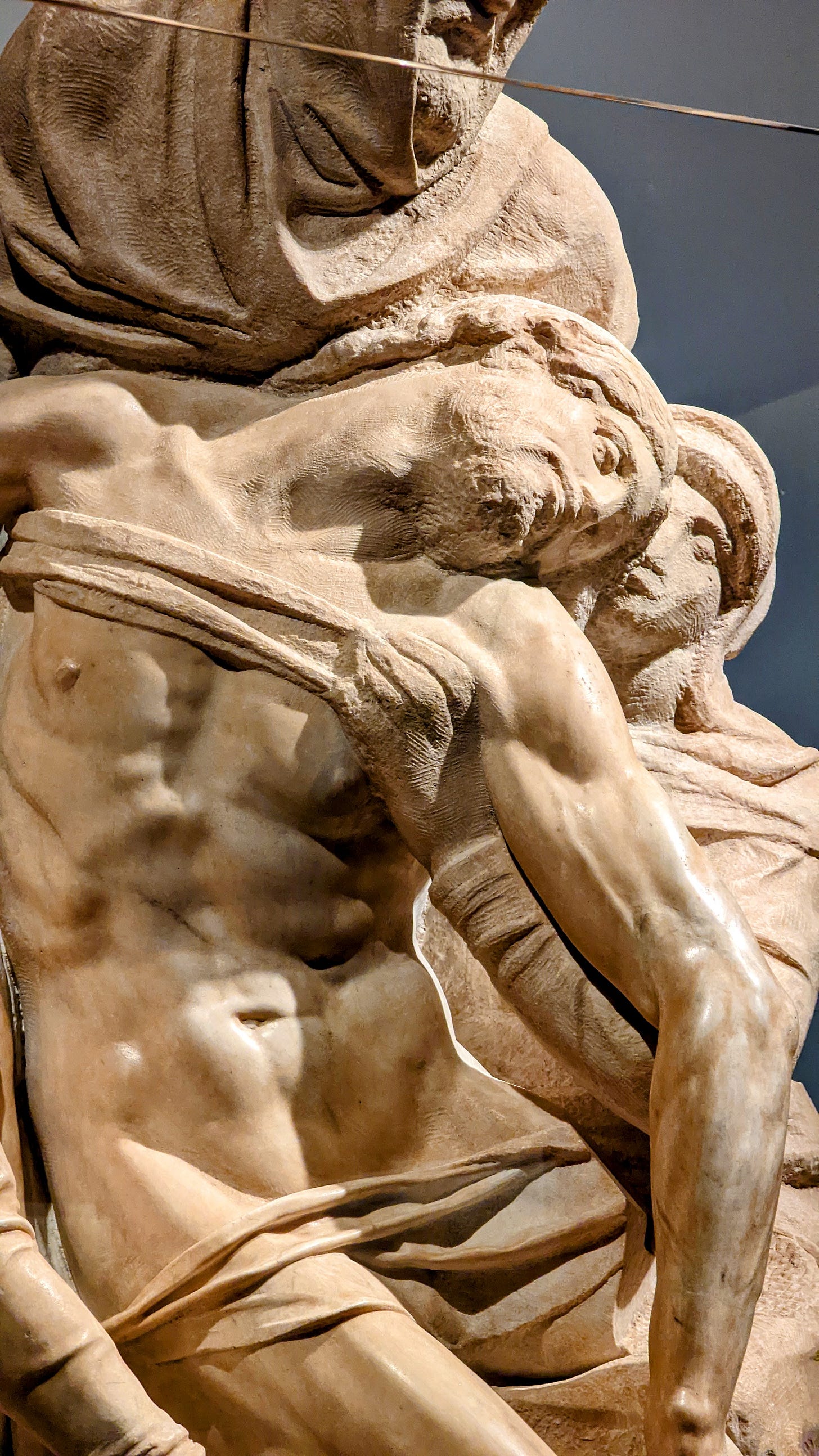

This Pieta now resides in Florence, in a small museum behind the Duomo. The Florentine Pieta [also called the Disposition] departs not only from the form of the Roman work, but also in the tone. Obviously, the figures are different. Besides Mary and Jesus there is a male figure in the back, likely Nicodemus, lifting Christ down from the cross by the band around his chest. The face of Nicodemus is Michelangelo’s.

In his earlier works, each person had their own psychic space, even when they were touching in some ways. In the Roman Pieta, the virgin looks down, seemingly lost in thought, upon the body of her son. But in the Florentine version, Mary’s [unfinished] face is pressed against Christ’s head in a passionate display of love and devotion as she reaches under his left arm to clasp the body being lowered from the cross.

Nowhere is the difference between the two pietas more visible than in the body of Christ [the only part finished]. Instead of the languid and passive tone of the Roman Pieta, here the suffering of Jesus is dramatic and centralized; The left arm is distended and torqued, the abdomen twisted and bent. The head slumped over.

Why the great difference between the two Pietas? Why the self-portrait? Most importantly, why did the great sculptor attempt to destroy his work, something he never did to any of his other pieces (though he left many unfinished)?

I do not know the answers to all these questions. The master did not often explain his artwork and actions. But I wonder if in the 50 years since he had carved the idealized perfection of the Roman Pieta, his ideas of what really constituted beauty had changed. He no longer saw the ultimate expression of the beauty of God in the idealized human body (as in the first Pieta) but in the broken and suffering body of the incarnate one, the God-man. A man in his 70’s has a completely different view of life than that same man in his early 20’s. For Michelangelo, I believe, the real beauty of God is not now seen in the perfection of the human body, that cosmic point of intersection between the realms of matter and spirit. Rather, God’s beauty is seen in the ugly, torqued and twisted body of the God who has died for us.

Reading further between the lines, perhaps he took up the chisel to erase his work because even his great skill was maddeningly unequal to the task of showing this beauty adequately.

As I say, I do not know for sure what went through Michelangelo’s mind. But I do know that as I stood before the Florentine Pieta, at age 55, it’s incompleteness, its unsmoothed chisel strokes, its broken beauty . . . all these resonated with the disillusioned, broken part of my heart more profoundly than the earlier Pieta ever could. I feel like a failure much more than I did as a young man. My aging body reminds me that I will never have time to make life what I want it to be, to make myself what I want to be. Perfection is laughingly out of reach; I grasp for adequacy. Regrets circle overhead like buzzards. But there is, by God’s grace, still a profound beauty in the brokenness. Ultimately, I have no power for beauty or rightness at all, except to, like Michelangelo in the sculpture, cling to the dying God.

Next to the sculpture is a sonnet inscribed on the wall; It is by Michelangelo, from about the time he was carving by candlelight this gravestone piece. As always, he sums it up better than any of us can:

So that finally I see

How wrong the fond illusion was

That made art my idol and my king,

Leading me to want what harmed me.Let neither painting nor carving any longer calm

My soul turned to that divine love

Who to embrace us opened his

arms upon the cross.

Wow, this piece is amazing.. The line, "Ultimately, I have no power for beauty or rightness at all, except to, like Michelangelo in the sculpture, cling to the dying God." really resonated. Thank you for sharing!